The AI Waterfall Trifecta: One-Shotting with TLA+, TDD, and Rust

Agile and AI

The Great Schism

Agile is dead. Not entirely, but as the de facto Right Way to Build Software™. As I’ve gotten deeper into agentic coding, it’s gradually dawned on me how much agile development sucks in the era of AI.

This is evident in the disconnect between vibe coders wowed by AI one-shot results and professional engineers who maintain mature production systems and remain skeptical. It’s because they’re both right: the more preexisting code the AI has to work with and substantially preserve, the harder you’ve made its job.

Think of it this way. If you tell me to build a boring CRUD app with a million different pages and features, I’ll find it mind-numbingly easy to build. I might need a Hyperbolic Time Chamber to get it done in a reasonable time frame, but I’ll be able to do it no question. If you hand me a 40-year-old codebase and tell me I need to build those features into that app, suddenly the cognitive demands go way up.

The New Math

For humans, time and skill level are both expensive. For AI, wall-clock time is almost free. You’ll have a very hard time attempting to construct a task that AI will need churn on for a month straight. Instead, the economic model is based on skill level and token consumption. That flips the dynamics of development on their head.

Agile works as a default for traditional human development in part because setting milestones for stakeholders to stay in the loop on progress is a logical method of keeping the project on track with few downsides. But there is still a major downside of agile, or more generally of developing requirements and implementation in parallel: the deeper you get into the project, the higher the marginal complexity of each successive milestone. Programmers experience this as the ninety-ninety rule.

Waterfall and You

LLMs as “Gigascale Decompression”

Which brings me to my thesis: in the age of AI, waterfall is the new best practice. When you need to launch in small steps and learn requirements as you go along, use agile. When you just need to build a known thing with well-defined requirements, it’s waterfall time. Iterating and revising requirements while an implementation has to play catch-up is expensive; iterating in natural language is cheap.

In most cases, natural language is simply more expressive than any programming language. Well-constructed and precise natural language encodes logic far more densely than code. In effect, natural language is the output of your brain’s compression algorithm for thoughts, and an LLM acts as a gigascale decoder for that compression. So long as you write at a level of abstraction that aligns with what a given model has sufficient knowledge to correctly infer the meaning of, you can write a spec with a high probability of being decoded into substantially similar code as you would have written by hand.

Diminishing Returns

This is all great for complete greenfield projects with no preexisting code, and no burden of strict backwards compatibility with preexisting APIs or UIs. However, the more legacy you accumulate, the more specific your required changes will inevitably need to be, and the less information-dense your natural language directives will become. To give an extreme example, if your task is to change the value of a specific known variable in a specific file, you’ll probably spend more time writing a prompt for that than doing it yourself.

Change requirements become lower-level because the moment you have an initial production implementation, the outside world begins drawing dependencies on its general stability and responsiveness to feedback. Launching a product starts a particular treadmill that will never stop for as long as the product continues to exist. Hence the cost of agile-style development.

AI Waterfall

Waterfall development targeted at agentic implementation is closely related to the recently popularized “spec-driven development” (SDD), but more narrowly describes iteration on a rigorous spec which defines the final expected end state of the new product/module, rather than an incremental change to an established system.

With AI waterfall, one natural question would be how widely to scope a single spec. For example, if you tried to one-shot a feature-complete AWS clone based on some sort of sprawling mega-spec, I imagine you’d most likely get a wacky result (unless techniques like context compaction and sub-agents work insanely well), and a half-decent result would likely heavily depend on strong organization and modularity of the spec. Scoping is ultimately a project management concern, but in extreme cases may need to be calibrated against the capabilities of the tooling itself.

The more pressing problem is that a high-quality spec merely has a “high probability” of being interpreted correctly. With competent humans and reasonable process, that basically doesn’t happen. If a human dev team were to accept ambiguous requirements and then hide in a cave and build the wrong thing end-to-end, it would mean many things would have had to have gone very very wrong. So how do we solve that with AI? The answer: feedback loops. If the machine is provided a means to detect flaws in its output, it can self-correct with no loss of valuable human time.

The AI Waterfall Trifecta

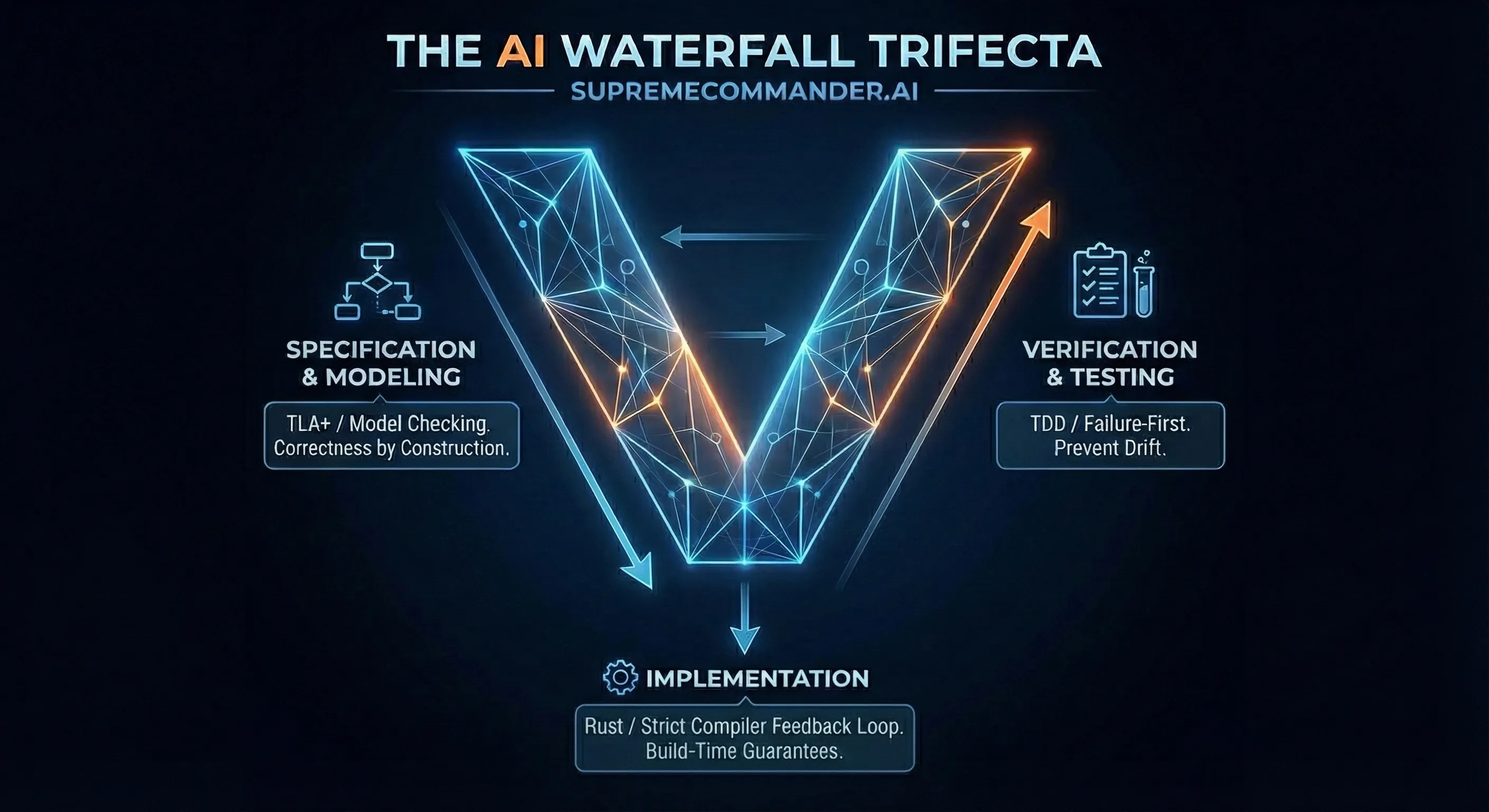

All of which brings me back to the title — to implement a durable end-to-end feedback loop for waterfall-based one-shotting with AI, I propose the AI Waterfall Trifecta:

Formal verification (TLA+). Specifically, formal verification of complex critical-path logic. You mostly hear about TLA+ being used in domains like kernel development and avionics, but it turns out there’s nothing crazy about it. While it has historically been considered extravagant for most purposes, what it functionally is is something like pseudocode (or meta-code) that can be validated against a set of assumptions/invariants regarding the effects of the logic. Writing reasonably competent TLA+ isn’t entirely beyond the capability of SOTA models. If there are bad assumptions in the spec or the agent’s interpretation of the spec, this is where the TLA+ tooling will catch those issues before a line of real code is ever written. Post validation, the known-good TLA+ encoding of the logic can then be used as a highly detailed and high-confidence subset of the broader spec.

- Credit to Martin Kleppmann for bringing AI-driven formal verification to my attention.

Test-driven development (TDD). After TLA+ proves the correctness of the critical paths of the spec, it’s time for the agent to build an expansive test suite that enforces compliance with the spec. We do this up front before implementing code to be self-corrected.

TLA+ on its own verifies only spec-level correctness. During the TDD phase, Kani should be used in order to create an implementation-level test (or “proof”) for each TLA+ specification. (Verus is another highly compelling option with some advantages in edge cases, but TLA+ with Kani provides most of the benefits and is likely simpler for AI to work with right now.)

In order to support exhaustively testing code before it’s written, one approach would be to have the agent’s roadmap direct it to stub out all files and interfaces with “not implemented” errors. This also serves as a useful planning step.

Build-time strictness (Rust). I used Rust as a stand-in for this due to its extremely expressive type system and compiler-enforced safety with minimal escape hatches, while still being highly practical with a thriving ecosystem. More generally, what I mean is that you want the strongest end-to-end correctness and safety guarantees you can get at build-time for a given project. Ideally: Rust if possible, or maximally strict compiler settings otherwise; strict linting / static analysis; and type-safe layers at I/O boundaries, such as Protocol Buffers and gRPC/ConnectRPC. This will provide a much tighter feedback loop than the tests, which eliminates entire classes of errors even along code paths that may have been missed by the test suite.

- Prior to pulling the trigger on this step, a manual human expert review is highly advised. By the end of phase 2, the only things that have been developed are ultimately just a formalization of the spec. Thus, it serves as a natural human review point. File paths, interface details, TLA+ specs, and test files are all useful artifacts to help evaluate for any potential mismatch in understanding of the requirements before giving the green light to implement. If the agent got it wrong, don’t proceed until it gets it right.

By stitching these approaches together, you provide an end-to-end feedback loop for the agent to validate its assumptions and output along every step of the way, and automatically pivot to correct mistakes without any human intervention. Forcing this level of rigidity onto a human process may be impractical without wheelbarrows of cash and a Time Chamber, but it’s what AI needs in order to thrive, and will actually save money by avoiding the trap of having it generate swaths of code that may not be needed in the final product.

How Well Does This Actually Work?

If you get a chance to try it out, feel free to email and tell me! Otherwise, stay tuned! I’m in the middle of wrapping up a spec for a non-trivial AI Waterfall Trifecta project, and eagerly look forward to reporting the results of my experiment in a follow-up post.